The power of teaching as inquiry

By Allan Powell on October 24, 2016 in Assessment for learning

I love visiting Year 1 classes. I’m always in awe of the skill and enthusiasm and energy of Year 1 teachers who provide students with their first experience of learning at school. I find it especially fascinating how these teachers teach students to ‘break the code’ of reading and writing – to create meaning out of lines and squiggles on a page. It is amazing and mysterious.

I’m working with one such wonderful teacher at the moment and want to share a cool story about her practice.

It’s a story about how a skilled and reflective teacher, through using a ‘teaching as inquiry’ approach, can solve issues for students who are struggling with learning in this very important first year of school.

I’m working in this teacher’s school to build students’ capability to be active/ self-regulating in their learning, because we know this leads to accelerated improvement. We’re using writing as the primary curriculum context to focus our inquiries and to monitor whether acceleration is actually happening. We’re also looking specifically at students who struggle with learning – the ones who are targeted in the school’s annual plan.

Let me introduce one of this teacher’s target students: Aaron wasn’t born in New Zealand and, while he speaks some English, he struggles with grammatical conventions – as any new learner of English might. Despite this, he is keen to share his ideas orally, which of course the teacher encourages with the enthusiasm I mentioned earlier. Aaron will draw superbly intricate drawings of his ideas and talk about them. When I first met Aaron, however, he simply wouldn’t attempt to write them down without knowing that he’d written it perfectly. Unless the teacher sat beside him and affirmed him every step of the way, Aaron would write almost nothing. He was definitely on track to be not on track after 40 weeks of school – especially the ‘independently and most of the time’ bit.

This Year 1 teacher sets individual or group goals with her students and this usually leads to quick and impressive improvement; by setting goals she takes all those skills that new learners of writing need and enables students to focus on one or two which will most help at that moment. These goals provide a clear and specific focus which really does help them to achieve success. Aaron has had goals such as ‘talking about my picture’ or ‘stretching out the word to write the sounds you can hear’ or ‘using the word cards’ (for common sight words). However, while Aaron has learnt to do these things that help him to write his ideas, as I said, he wouldn’t do them without an adult right beside him, assuring him that his writing is ‘right’. The other skill he has is using all his five-year-old charms to inveigle adults into helping him! I have been a victim of these charms when visiting his classroom!

This teacher and I have had such interesting discussions about Aaron, and her other target students. We employed an inquiry approach to figure out how to make a difference for him, because the teacher’s current approaches, which are very successful for many, were not proving successful for Aaron. This seemed highly important to inquire into.

In the teaching as inquiry process, the key for me is always the ‘focusing inquiry’. The focusing inquiry is all about drilling down to figure out what the real issue might be. It’s about making sure you understand the issue deeply before jumping to a solution. In doing this, the teacher and I started by listing all the things Aaron could do (when the teacher was with him).

Plan (with a drawing) and talk about his plan.

Say an idea from his plan to the teacher (“I have got five cars.”)

Figure out how many words there are in the idea.

Remember his idea and keep saying it as he writes.

Leave spaces between words.

Stretch out the words he doesn’t know and identify at least the beginning sound.

Find words on word cards and in books and on the wall (he is really good at this).

He could do lots!

Then we thought about what he couldn’t do that was particularly holding him back. We already knew that Aaron wouldn’t try without the teacher’s support, but we set up an observation of what he actually did when that support wasn’t there. During this observation, Aaron started with gusto until he got to the first word he didn’t know how to write (it was the third word). He said the word slowly and identified the first sound, but wouldn’t commit it to paper. He then went looking for the word around the classroom – in books and on the walls – but when the teacher wouldn’t confirm if it was the right word he wouldn’t write it down. So we learnt that he could use the strategies independently, but wouldn’t put any of his strategies into action by himself. He wasn’t willing to make a ‘mistake’. He wasn’t being an independent learner.

The teacher and I discussed our ‘hunches’ as to why Aaron won’t try for himself, and decided that one reason might be that he doesn’t know how important it is to try for himself – because the teacher hadn’t told him. Perhaps he believed that being a successful learner is about getting everything right, whereas we know that trying for yourself, and not always being 100% successful, is vital for learning to happen.

So, we decided to experiment by throwing out Aaron’s other goals and setting a new one: Great learners try all by themselves.

The teacher wrote this new goal in Aaron’s book, and got him to draw a picture of what trying by yourself looks like, so he’d remember his goal. She talked about it a lot. She got Aaron to share his goal each day with her and others. She gave him feedback only about how he was trying by himself. And she toughened up to Aaron’s requests for constant affirmation. One day, shortly afterwards, Aaron, all doe-eyed, asked his teacher imploringly, “Why aren’t you helping me?”. The teacher’s response: “Because great learners try all by themselves, Aaron, and you are a great learner! You can do it!”.

Here’s the impact of the teacher’s deliberate inquiry into Aaron’s writing development.

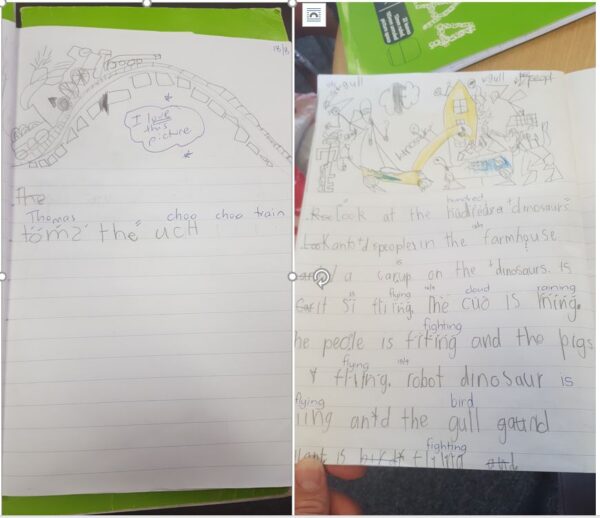

In August, the image on the left was typical of what Aaron would write when not with the teacher. The image on the right shows Aaron’s writing three weeks later. It was the culmination of a few writing sessions, but Aaron did it with no support at all from his teacher.

This wonderful teacher was so excited to show me the improvement Aaron had made the next time I visited the school, as was Aaron. I was a little dumb-struck, to tell the truth. I had seen this boy sit for an entire writing session stuck on one word, and here he was writing, fully independently, about the pigs and the robot dinosaurs flying above the ‘peoples’ in the farmhouse!

Finding the right goal for Aaron – the thing that was holding him back – had ‘unlocked’ his learning.

Below are the questions that we used to unpack the ‘focusing inquiry’. You might like to use them when you come across a student or group of students for whom your usually effective strategies are not working. I’ve included some examples of how we answered these questions, which repeat a bit of the information above, but give an idea of how we worked through the inquiry systematically and purposefully.

What is most important to inquire into given where my students are at?

Aaron’s writing development.

Why is this inquiry important?

He is definitely not progressing in his writing, despite my spending a lot of time supporting him. My current strategies are not helping so we need to try something different.

What evidence has led to this inquiry?

Teacher observation – Aaron always wants confirmation that he is ‘right’. Also, there is a huge difference in his book between teacher-assisted (and teacher-aide-assisted) writing and when he has written without support.

Which students are the focus of this inquiry? For which students is this not an issue? Why might that be?

Most students are focusing on their goals and writing independently, but Aaron is not. I don’t know why – that’s what I want to figure out through this inquiry.

What can the students do that we could leverage off?

When assisted and prompted, Aaron has lots of strategies – e.g stretch out unknown words, use word cards, etc.

Do I need to gather more evidence about the issue for these students?

I need to see if Aaron is using any of the strategies when he’s not with me. Is it that he doesn’t understand the strategy or that he can use the strategy but still isn’t writing?

What are my current theories (hunches) about why this issue exists?

Our hunch is that he doesn’t understand that learning involves trying for himself and sometimes not being completely right.

What alternative theories (hunches) might be true?

He may not understand the strategies I’m teaching him and he needs more support and scaffolding with these.

How might I (the teacher) be contributing to the issue?

I haven’t talked to him about how important it is to make mistakes when you are learning and to try by yourself. I’m probably also helping him too much!

What other perspectives would help me understand the issue (students, parents/whānau, other teachers)?

I’d like my DP to come in and watch what he does by himself. If I am anywhere near then he’ll wait and wait for my support. I’d like her perspective.

Hopefully you can see how working through these questions really helped the teacher and me ‘drill down’ to identify the issue and decide on what to change. Maybe working through these questions might reveal the changed teacher strategy necessary to unlock learning for a student in your class.

Other articles you might like

Teaching as inquiry, in my mind, is a relatively simple concept that has been made more complex and less effective by the perceived demands of compliance.

Where to start? What and how much do we need? Questions schools are asking about Literacy support.